|

| bpNichol's famous The True Eventual Story of Billy the Kid in its original chapbook form. |

"I like narrow-casting, if by that you mean smart content aimed at a small audience." - Nick Carr

*

First some thoughts on small press publishing, then HOW TO CREATE A CHAPBOOK without creating X-Acto knife finger snowflakes.

*

Publishing is not a neutral act. It is implicitly political and aesthetic. The publishing is part of the aesthetic of the work, in terms of its look, its distribution, and how the audience interacts with the work, both in terms of reading it, engaging with its writers and publishers, and in how it finds its audience. In the small press, there is a reason, a conscious decision, to publish the works in the way that they do. The presses choose to publish in this form not because they have to, but because they want to. In this kind of publishing, success is defined as an authentic interaction between engaged writing, publishers, and readers.

Charles Bernstein:

The power of our alternative institutions of poetry is their commitment to scales that allow for the flourishing of the artform, not the maximizing of the audience; to production and presentation not publicity; to exploring the known not manufacturing renown. These institutions continue, against all

odds, to find value in the local, the particular, the partisan, the committed, the tiny, the peripheral, the unpopular, the eccentric, the difficult, the complex, the homely; and in the formation and reformation, dissolution and questioning, of imaginary or virtual or partial or unallowable communities and/or uncommunities.

*

more Charles Bernstein on Small Press :

Intellectuals and artists committed to the public interest exist insubstantial numbers. Their crime is not a lack of accessibility but a refusal to submit to marketplace agendas: the reductive simplifications of conventional forms of representation; the avoidance of formal and thematic complexity; and the fashion ethos of measuring success by sales and value by celebrity. The public sphere is constantly degraded by its conflation with mass scale since public space is accessible principally through particular and discrete locations.

*

CHAPBOOKS!

The final assignment for this class is to create and hand-in a chapbook consisting of several poems written and revised during the class.

A chapbook is a simple form -- though one extensively used -- to present short poetry or fiction publications. They can be created simply and functionally or made into beautiful book objects, using fine papers, handmade elements, letterpress printing, hand binding, and many other highly developed or varied elements. They come in numerous sizes -- from tiny books to huge swathes of paper.

For our purposes—unless you are so motivated to make your chapbook a monument to super-gussied-up real purdy-fine fine art-like fanciness—a basic chapbook will be sufficient.

A standard letter-size printer paper (11" x 8.5"), printed landscape, two sided, and folded in half and stapled or sewn is a pretty standard size to make chapbooks out of.

When you print a folded booklet (like a chapbook) you need to assemble the pages so that the right page prints on the right sheet of paper. Creating a paper-mock-up of your chapbook is invaluable in helping you figure out which way is up, or your verso from your recto.

However, Adobe Reader, through the gobsmacking wonders of MODERN TECHNOLOGY, can compile it for you.

Here's how:

Create your chapbook with each single page as a portrait-oriented 11 x 8.5" pages and then save it as a PDF file. Then open the file in Adobe Reader.

If you select the "Booklet" feature—hey presto, Stephen Harper's hairspray—it will automatically compile your file into a landscape-oriented and ready-to-print file.

You can print out your booklet and it will be ready to photocopy as a chapbook. (You just have to make sure to get the right backside of the page together with the front. It's like dancing.)

If you'd like to print your booklet out on a printer, you can select the "Booklet subset" button and choose "Front side only." Print this. Then stick the printed-out pages back in the printer in whichever way your printer requires you to do so to print on the back side. (This may take some fiddling around and trial and error to figure out which is the right way.)

Now select "Back side only" back at the Booklet subset button on Adobe and print away. The book should now have both pages printed appropriately. All that is required is to fold the pages and staple (you'll need a long-arm stapler) or to sew the spine (the fold._

Here is an MS Word DOC Mock-up of a Chapbook. You can substitute your content for what's here and then safe as a PDF.

Your saved PDF should look like this PDF Mock-up of Chapbook. You can follow the above-noted procedure to print it out into a snazzy chapbook.

The first page—and the back of it, pages existing, at least in the real world, in three dimensions—is intended to be for the cover page. It'd be a good idea to print this on some thicker cover stock, and likely, in a colour. It can be a nice effect to stick in a contrasting blank colour page (non-cover stock) between the cover and the white pages as a kind of flyleaf.

*

Activities

1. Ekphrastic verse. Write a prose poem based on one of these images. You can be inspired by the general mood and/or specific details in the images. You can take the point-of-view of anything in the image or anything outside the image. Or you don't have to have a coherent POV at all.

a. Cloud

b. The Lost Jockey (Magritte)

c. Skeletons

2. Write a line which includes something happening. Now write the same line at least ten different ways, using synonyms, figures of speech and all sorts of varieties of circumlocutions in order to same the same thing in different ways in each sentence. (I stole this exercise from writer/writing teacher Stuart Ross. Link here.)

14 times the same line

|

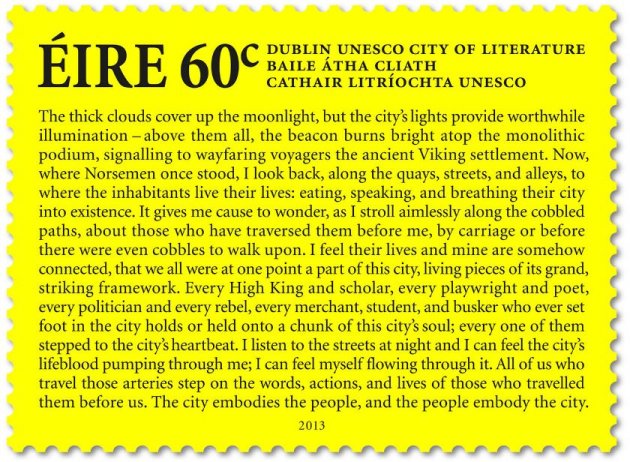

| Irish stamp features entire prose poem |

4. Write a prose poem in which there is some non-standard grammar (a 'grammar mistake') in each sentence. Non-agreement of subject and verb, of verb tense, of plural. Whatever non-normative 'mistake' that you want. How does this affect the poem? How does it affect your writing process? How does it affect how the poem works or the 'voice(s)' of the poem?

No comments:

Post a Comment